| Lorenz Estermann |  |

| home |

| news |

| info/press |

| links/contact |

| gallery/archive |

| sculptures |

| imprint |

| works on paper |

| books |

| Simon Baur (Basel) und H.P.Wipplinger (Vienna), 2008 Katalogtexte >instant city< (english) | |

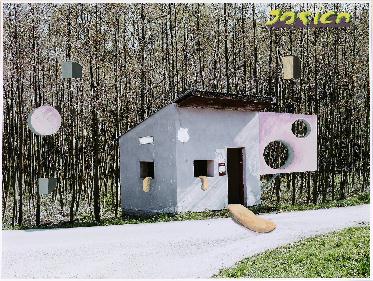

Simon Baur: (Translation by Sean Gallagher) Empty spaces between the words Lorenz Estermann's conception of models They appear again and again, these three pictures of the Città ideale, a broadly conceived project that could be approximated in painting, but which was never built due to the knowledge that reality and the ideal are two different things. Part of these pictures' mysterious charm is that their authorship is disputed to this day. Three names are identified in the research: Piero della Francesca, Luciano Laurana, and Francesco di Giorgio Martini. The intentions of those who commissioned them can also not be fully resolved. The paintings by these >anonymous authors< are constructions - executed only inceptively in a few Italian cities - as envisaged by painters, architects, city planners, and even rulers during the Renaissance. What is there to see in them? In the first painting a triumphal arch, through which one looks out at a tower and a landscape view, stands between an amphitheatre and a baptistery. In the foreground is a broad plaza with columns and a fountain. In the second painting a baptistery occupies the central axis with residential buildings and wells to the left and right, and a basilica in the background. In the third picture an arbour opens out onto a plaza with buildings, while on the horizon one sees a harbour with ships. Streets - mostly only suggested or exhibiting the dimensions of boulevards or even plazas - function in these paintings as empty spaces to separate the stately buildings from one another, and allow a view of the attractive facades. Yet all of these are clear (in the literal sense) and important elements of the group, like in an open-air museum, a world exhibition, or the Venice Biennale. The contradictions in the foregoing sentence were deliberately formulated. Distinguishability is ensured, and theatre venues can be discerned from sacred or public places, just as the German pavilion at the Biennale looks different from the American or Hungarian ones. (It is less about being important as about being obvious). There is a conceptual relationship between the pavilions at the Biennale in the Venice Giardini, and the vistas of the ideal city. Here both are types of ghost towns, with buildings that consist only of facades. Heating systems, bedrooms, and kitchens are missing from these buildings, and they are like a town one travels to only as a summer resort, but which stands empty for the remaining time. Alpine summer pastures [Maiensässe] and Alpine huts have a similar fate. In the ideal cities are no signs of people or life; these are only hinted at, such as by the ships in the harbour. Ephemeral habitations In this context one is justified in asking whether and how human habitations, such as apartments and houses, have undergone a shift in values over the past years. Modern nomadism, continuous mobility, and increasing expectations make us realize that the definition of residing, of being situated in a location, has been subject to a process of transformation for a good twenty years. The dream of a privately owned home has become a realistic possibility, and anyone who travels the entire day wants to enjoy anonymity and peace at home in the evening. Increasing tolerance of others makes it possible for everybody to create their own domicile, be it a castle, a villa, an apartment, a hotel room, a mobile home, a yurt, a tent, or a hammock. Seeing a new hotel room every night and living out of a suitcase is as much a reality as is the familiar marital bed. These changes in lifestyle habits have also always been thematized by artists. Andrea Zittel, Thomas Hirschhorn, and Erik Steinbrecher demonstrate how this can function, and how much has remained the same despite global interconnectivity. Et ego in Utopia In this context it is not insignificant to establish the premises under which the above processes and developments have been absorbed and accepted. Could it not be the case that contemporary society finds itself in a process of change, the duration of which is set as decades - and is therefore barely perceived by individuals - and which contemplates a transformation of the res publica in the sense of Thomas More's Utopia. This visionary book is still worth reading, and its relevance here is summarized in the following. The Utopians live in their cities in groups of families, and sexually adult persons enter into monogamous marriages. Dominating overall is a patriarchal hierarchy, with older people in charge of the younger. Beyond the families the community is organized like a monastery, with a communal kitchen and collective meals. A superintendent elected yearly supervises a family grouping of thirty families. Private property does not exist and everybody is given, free of charge, those community-produced goods they desire for their personal use. Men and women work as craftspeople six hours a day, and citizens are free to decide which craft they will be trained in. Citizens are required to work, and the Utopians are regularly sent to the countryside where they perform communal agricultural work. Children are required to go to school. Particularly talented people receive scientific or artistic educations. Scientific lectures are open to the public, and attending these lectures is the most popular leisure activity of the Utopians. The citizens especially value the provision of optimal medical care for every sick person. Men and women regularly train for military service. War criminals and other criminal offenders, sometimes purchased from foreign countries as persons sentenced to death, must perform forced labour. Religious tolerance reigns in this secularly organized community. The state is a republic. Every city is ruled by a senate composed of officials elected for a limited term. The head of state is elected for life. Important decisions are made by popular referendum. Among the Utopians themselves there is no money. Through overproduction of goods they accumulate much of this, however, and use it to operate mercenary armies or for trade. The Utopians do not value gold. Cities may only attain a stipulated size. Overpopulation is balanced by migration or by the formation of a foreign colony. Conversely, in the case of a lack of inhabitants, a return flow takes place from colonies or overpopulated towns. Does this not sound like the World Wide Web (www.), like minimum wages and universal health care, like union thinking, like EU, Euro, Al Kaida, Nato, or Opec, like Guantanamo Bay and religious freedom? Some people are amazed at the similarities, others become angry at the absurdity of the comparison, yet it is exactly this contrariness, this impossibility of precise definition, which I am aiming at. The Biennale, the ideal city, the open-air museum - and the changing concept of society - are all characterized by a common denominator: they are models. What is a model? The word has roots in Renaissance Italian as the word modello, derived from the Latin modulus, a scale in architecture, and it was used in the fine arts as a technical term until the eighteenth century. Herbert Stowiak suggested a general theory of models in 1973, and it was adopted by many researchers in the field. Not specific to any one field, this conception of models is generally applicable. It is characterized by three features: 1. Illustration. A model is always an illustration of something; it is a representation of a natural or artificial original, which itself could in turn be a model. 2. Abbreviation or simplification. A model does not comprise all of the original's attributes, but only those that appear relevant to the model's designer or user. 3. Pragmatism. In general this means an orientation towards the useful. A model does not intrinsically correspond to an original. The correspondence is qualified by questions about who the model is for, about its use, and about its users. A model is used by the model designer and model user within a stipulated time period and for a particular purpose. Because the model is an abstraction of reality, it allows the creation of a simulation and an interpretation, and perhaps also of a vision. (vgl. ) In the intermediate zone The detours through ideal cities, Utopia, and models were necessary because they are all components of the complex structure of Lorenz Estermann's works. He began with drawings in which he used photo-monotype to include motifs of houses, huts, or ramps. In these works the graphical elements combine with additional image motifs, providing no unequivocal reading or narrative message. They are more like collaged plans: >The truth is that the models or room segments were created purely by considering their merits as drawings. This is also because I basically regard myself as an artist working in the medium of drawing, who sidesteps into three-dimensionality in order to bring the results back into the two-dimensional<, as Lorenz Estermann explains his approach. He initially builds the motifs he derives from his drawings as small models - more recently even as large models - made of plywood and cardboard, painting them then to look like older buildings on which can be seen the ravages of time. Lorenz Estermann: >I see the surfaces of the large and small models as being open for my painterly strategies, and use them very consciously with this in mind. The remains of my ?painterly' past are now the surfaces of the objects.< Assembling objects and combining them with painterly traces - Lorenz Estermann thereby speaks of >instant architecture< - which sometimes also allow one to make out real motifs, is reminiscent of the most recent works of the American Frank Stella, who creates spatial formations from painted strips of metal, and Stella's works in turn are reminiscent of Vladimir Tatlin's counter- and corner-reliefs. Yet between Stella and Estermann - as explanatory as the comparison may be - there is an evident difference. While Stella's works are specific objects in the Minimal Art sense, in Estermann's works a feedback takes place involving both the object and the image. The objects are models and as models they have an autonomous character. At the same time the motifs act as models for new objects or drawings. The strategy of slurring Yet not everything is explicit, and one can still find empty spaces in Lorenz Estermann's work. The work cannot be clearly classified as painting, as object, or as architecture. It is just as impossible to classify the models. This does not mean, however, that we cannot read the works - they certainly are understandable - and still more they appeal simultaneously to both intellectual and to sensual experience. Yet my ideas and explanations are also characterized by empty spaces between all the words, and while these do not obscure the words' sense, they also naturally do not explain all meaning in the words of the text, nor all meaning in the works of Lorenz Estermann. Wittgenstein wrote at the conclusion of his Tractatus logico-philosophicus: >The inexpressible certainly also exists; it is shown, it is the mystic.< (6.522) With this we are very close to the strategy of Lorenz Estermann. In his technique the seams, imprecise transitions, and even the meanings of words and their pronunciations are slurred. In this text that kind of slurring would have devastating consequences. The words, sentences, and sections in their totality would unite into a single, and thus unreadable and even unpronounceable concept (whereby this would have the character of a model). Methods, techniques, concepts, and ideas allow themselves to be slurred in art. Drawings, architectures, and paintings are objects and thus models, but simultaneously they are also illustrations and conceptions of something new. This is because art, besides its reality, is also always simulation, interpretation, and vision, and so not only, but also and above all: a model. Simon Baur ____________________________________________________________________ Hans-Peter Wipplinger: (Translation by Sean Gallagher) Ergonomics of architecture Perceptions and comments on the built environment in the work of Lorenz Estermann Crystallizing for some time now in Estermann's artistic production has been an important leitmotif of de- and re-constructed >architectures<, which he brings to realization as drawings and paintings, and also in the form of models. These are creations that take on unconventional identities, setting memory mechanisms in motion, and evoking narrations. The phenomena thereby initiated - with particular regard to their aspects of aesthetic, ergonomic, and spatial design - shall be echoed fragmentarily in this article. First and foremost are economic and culture-political conditions that cry out to be dealt with, and make reference to the epoch of industrialization or the Industrial Revolution. They thus refer to a historical phase that not only greatly changed communication and transportation technologies, but also and above all significantly influenced the system of construction and the erection of architectures. The redefinition of space accompanied these developments, and naturally this was just as true in urban locations as in secluded rural regions. Estermann begins here with his artistic investigations, by going >hunting< for images. On the one hand this hunt occurs as research, in his intense study of literature and magazines from the nineteen sixties and nineteen seventies, and on the other hand it takes the form of extensive field expeditions that sometimes occupy him for weeks, principally through Eastern European countries. His personal archive of pictures and literature form the starting point of his search for meaningfulness and functionality, and for forms of manifestation and representation of the built environment. In this working process he consequently asks questions about our society's cultural, psychological, and not least sociological states, the architectures and therefore spatial productions of which are naturally mirror reflections or illustrations of societal change. Cubic space and constructed spatial volumes have the special property of storing culture-historical states and historical experiences and thus, as silent witnesses to the past, of conserving a form of stone, glass, or steel documentation in which history manifests itself. This storage capability of the built environment also, through its ability to absorb temporal phenomena, allows conclusions about culture-historical states to be formed, and sends us messages, like linguistic notations in the form of architectural images, about these. In this context one thinks, among other things, about economically influential aspects such as consumption, leisure time, and tourism, whereby postmodern architecture in particular increasingly functions as a marketing tool in the sense of providing touristic sensations. Architectural icons are being created everywhere in this manner by world-famous and globally operating architects. The more unusual their signature >pictures< seem from the outside, the greater the spectacular mark they make (which includes indirect economic returns). Yet Estermann's designs and models do not at all illustrate that contemporary glass and steel high-gloss aesthetic, so well known in the media, of the architectural landmark. For this the Estermannian constructions seem too unconventional, non-functional, and poor in terms of materials, and thus seem much too much to be from a different world or a distant (seemingly avant-garde) time. It is precisely such inconspicuously casual and forgotten structures (or eyesores) that Estermann adopts, raising or stylizing them to the status of unusual sculptures with a high potential for aura and sensuality. Viewers ask themselves whether the artist, with his subversions, may even be trying to express an idea of romantic reflection. As unsightly and shabby as the real architectural >models< may seem, they do exhibit a simple sublimity. But what, per se, defines the sublime or beautiful in a piece of architecture or sculpture? Using precisely this methodical trick of deconstruction and reconstruction Estermann makes tongue-and-cheek reference to the structural changes taking place in planning, building, and using, thereby transforming the theoretical analysis of man-technology-systematic or user-object-relationship into a conscious or unconscious experience. With the advent of the concept of design, the interface between people and technology in an ergonomic sense was first subjected to more intense scrutiny in the Bauhaus, later to be developed further by Californian product designer Henry Dreyfuss not just in the sense of design, but also in terms of the serviceability of products. Back to Lorenz Estermann. Photographs of real situations are generally the starting points for his artistic investigations both in the areas of drawing or collage, and for his model-like constructions. Thereafter follows a process of blending out fragments, adding formal scenic props, and placing dramatic (and sometimes absurd) architectural gestures. The various elements of the structures display both visible appurtenances in the form of strange projections as well as radical reductions, which lend a playful ease to the stability of building features. Estermann's revisions permit a questioning of the structure's purpose, use, aesthetics, and not least its placement in space and its historical contextualization. The result of this strategy is the accentuation of particular components and subsequently the recombination and recreation of meaning. While structuring the coverings or surfaces of his models the artist works with materials such as cardboard, plywood, and paper, the surfaces of which he draws or paints upon with a hint of a grubby aesthetic, so that they radiate a simple and unspectacular aura. In attitude they seem fragile and hardly prestigious; the usual sense of the durability of constructed monuments is replaced by transitoriness and instability, and this is fundamentally due to the nature of the buildings. Obliteration, emptiness, and nothingness in the form of formal reductions are those metaphors with which the artist creates open zones and in this manner precisely focuses upon the ?different' by means of omissions and the creation of empty spaces. In this way Estermann redefines buildings and spaces, thereby generating possibility space. Fiction consciously remains fiction in Estermann's work, and he has no intention of becoming an architect or designer himself, but on the contrary of devoting himself completely to the luxury of artistic design and aesthetic composition. Viewers, confused but sometimes also amused, are left faced with Estermann's seemingly grotesque, deforming interventions. Viewers get a sense that these bold formations could not function in this way, if one considered, for example, the statics of various building constructions. The characteristics of the categories mass and weight are thus taken to the point of absurdity. Solid structures sometimes seem to float as if the law of gravity - which holds not just for architecture but for all life on the planet - had been suspended, thereby putting everyday causation and normality into perspective. These manipulations of Estermann's, which sometimes seem like fluttering illusions that set the laws of physics and logic out of force, are reminiscent of earlier collage-like photomontages (>Transformations<) made by Hans Hollein in the nineteen sixties, in which he integrated strange objects like airplane wings, a radiator grille, etc., as architecture in landscapes or in a cityscape. Similar to these Holleinian >Transformations<, Estermann almost mischievously plays cat and mouse with the viewer's reception and perception. In his models and drawings the most inconspicuous and desultorily objects and architectures develop metaphorical potential. Soberly cool phenomenology becomes not only a witness, but simultaneously an interpreter of history. Estermann documents these contemporary radical changes from the subjective viewpoint of a tracker, firstly as mentioned through photography, and then by constructing models and drawings. On this hunt he encounters forgotten and sometimes long-neglected places. Thereby he practices a very personal type of field research: research into his own thinking, and also research into a world-oblivious no man's land, which is subject to constant change. Through his artistic interventions he awakens things out of their sleep and brings them back to life, and they tell bizarre, ironic, and always unpretentious stories. Although human beings are generally excluded from his work, it inevitably provokes viewers to follow the artist's train of thought on the sociological level; indeed the shell-like buildings also condition a concrete form of work and life, which one inevitably understands and expands upon. Consequently Estermann also appears concerned with capturing the tangible structures and landscapes of no man's land, and this also creates psychological spaces which present themselves more or less soullessly to viewers. Estermann's unconventional superimpositions and thus relativizations of virtual and real architectures, as well as of fictitious spatial constructions, negate conventional definitions of space, allowing new spatial structures and typologies to arise. His seemingly minimal artistic works analyze the transformation of architectures, spaces, and infrastructures, becoming sculpturally hypertrophic and ultimately then, a concisely presented, new type of fictional sculpture and three-dimensional object. In an era of globalized virtual spaces, Estermann provokes questions about the direct environment and about architectures, places, typologies, morphologies, landscapes, and not least identities, all of which significantly condition our (living-) spaces and thereby our existence. With this, Estermann creates new possibility spaces and ways of looking at things. From viewers, these demand new perceptual and intellectual efforts in order to recognize the utopian disassociation of his designs and to divine the multilayered meanings of his transformations, behind which is hidden the adventure of the altered view of figures, sculptures, three-dimensional objects, and form. Hans-Peter Wipplinger >It is not enough to please the eyes; [Architecture] must touch the soul< Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières (The Genius of Architecture; or The Analogy of that Art with our Sensations, Santa Monica, 1992) |

||